Did you know that the Royal Mint only issued its first Christmas coin in 2016? The £20 silver coin featured a nativity scene by Bishop Gregory Cameron in which the baby Jesus is shown on his mother’s lap as the Magi present their gifts. Astonishingly, it remains the first and only time in the mint’s thousand-year history that Christ has ever been depicted on a British coin, and special permission was obtained from Her late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II to do so.

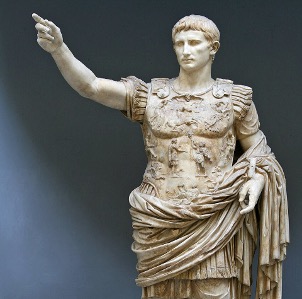

But what if I told you that the world’s first Christmas coin might actually date back over two thousand years? I’m fortunate to own a Roman silver denarius from Rome’s first emperor, Caesar Augustus, who reigned from 27BC until his death in 14AD. This coin, struck between 2BC and 4AD, doesn’t show the nativity, the Magi, or any traditional Christmas imagery. Yet, I believe it could be deeply connected to the story of Christ’s birth.

In the New Testament, Luke’s biography of Christ describes how he came to be born in Bethlehem. He explains that Caesar Augustus issued a decree that a census should be taken of the entire Roman world, and that people travelled to their ancestral homes to register. For Joseph, this meant taking his heavily pregnant fiancée, Mary, on an eighty-mile trek from Nazareth to Bethlehem.

Augustus was known for conducting several empire-wide censuses. The Roman historian Tacitus wrote that he “recorded by his own hand the resources of the state, including its number of citizens”. Censuses conducted in 28 BC, 8 BC, and AD 14 showed that the number of Roman citizens in the empire was increasing. Augustus proudly records these numbers in his autobiography Res Gestae (Acts or Achievements), which he wanted inscribed on pillars in front of his mausoleum in Rome after his death.

There is no suggestion that any of these three empire-wide registrations involved counting non-Romans, which makes them unlikely to have involved Mary and Joseph. Besides, none of these census dates corresponds to the likely date of Christ’s birth. Luke tells us that Jesus was about thirty years old when he began his public ministry, and that this occurred during the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar (28-29AD). Working backwards, this would suggest that Jesus’ birth was around 2BC.

Here’s where it gets interesting. In his list of achievements, Augustus records that “while I was administering my thirteenth consulship (2 BC), the Senate and the equestrian order and the entire Roman people gave me the title of Father of my Country”.

This title, bestowed on the emperor after a long period of peaceful rule, could be highly significant in our attempts to determine the circumstances that brought Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem. The honour was celebrated throughout the empire, and everyone was expected to affirm Augustus in his new paternal role as their protector. Such an affirmation would have required a massive registration of people throughout the Roman world, exactly as Luke describes it.

The first-century Jewish historian Josephus appears to reference this event in his work Antiquities of the Jews, where he states, “When all the people of the Jews gave assurance of their good will to Caesar, and to the King’s government; these very men [Pharisees] did not swear: being above six thousand”. His statement that over 6,000 Jewish religious leaders did not affirm Caesar when required to do so only makes sense if there had been an empire-wide affirmation that counted every response.

Rome allowed member provinces to observe local customs when it came to following the orders of the occupying power. For example, Josephus records that the Romans allowed Jews to maintain tax exemption every seventh year and observe their holy days. If there were a requirement for Jews to assemble in their homes to be registered, under Jewish culture, people would want to travel to their ancestral homes to be counted. This would appear to have been acceptable for an emperor who wanted people living in his empire to affirm his title as ‘Father of the Country’ (‘Pater Patriae’ In Latin).

The silver denarius struck in 2BC proudly recognises Augustus’ new title as Pater Patriae. The reverse depicts his two grandsons, Gaius and Lucius Caesar, whom Augustus adopted and designated his successors. Sadly, within a few years of the coin being issued, both young men were dead, leading the emperor to appoint his stepson, Tiberius, as his new heir in 4AD.

It remains an intriguing possibility that the honour celebrated on this silver denarius may have set in motion the chain of events that led directly to Jesus being born in Bethlehem. Whether or not this was the case, one thing is certain - the coin circulated widely throughout Judea and the rest of the Roman world, making it a piece of history that Jesus would have known well.