The Penny Post - A Revolution in Personal Communication

Did you know that Great Britain is the only country in the world that doesn’t put its name on postage stamps? This is because the world’s first self-adhesive postage stamps were issued here in 1840. Sir Rowland Hill's invention of the Penny Post made sending letters and parcels more affordable than ever before and sparked a revolution in the way people communicated with each other across the world.

The English postal system began in 1516 under King Henry VIII and was initially created to serve the monarchy and government, enabling secure and swift communication between dignitaries. Messages were carried by royal messengers or courtiers, and the system was not available to the general public. During the seventeenth century, postal routes and relay stations were established throughout the country, and King Charles I made postage available to anyone who could pay for the privilege of receiving a letter. However, the system remained prohibitively expensive, and therefore available only to the wealthy.

In 1660, King Charles II established the General Post Office but the service remained disorganised, chaotic, inefficient, wasteful and expensive, with the payment required to deliver a letter or parcel paid for by the recipient and not the sender. Postage was charged based on the number of sheets of paper used and the distance it travelled.

By 1840, the cost of receiving a letter sent in Scotland was 2 shillings (24 old pennies), which could be half a day’s wage for some. To save money, people would fill up the space on a page by writing in two directions and mark the letter with coded symbols in case the recipient lacked the funds to purchase it. For example, an ‘X’ in the top-left corner meant ‘in good health.’

In 1837, an English teacher and inventor called Rowland Hil (1795-1879) published a radical idea to reform the postal service. He sent a copy of his pamphlet, called ‘Post Office Reform: Its Importance and Practicability,’ to the Chancellor of the Exchequer and was promptly invited to a meeting to discuss his ideas further.

It is said that Hill had become disillusioned with the postal service after overhearing a young woman who was too poor to pay the postage for a letter sent by her fiancé. As a result, her letter was destroyed unread. He considered this to be an inadequate way for a civilised society and a rapidly expanding nation to behave.

After his first proposal was rejected, Hill revised his plan and Parliament ultimately approved his simple yet profound solution: a uniform, prepaid postage rate of one penny, regardless of distance, making communication accessible to rich and poor alike. Hill reasoned correctly that the new prepaid system would make the postal service more profitable and efficient, as it would dramatically increase the number of letters sent, which would in turn pay for the infrastructure required to deliver them.

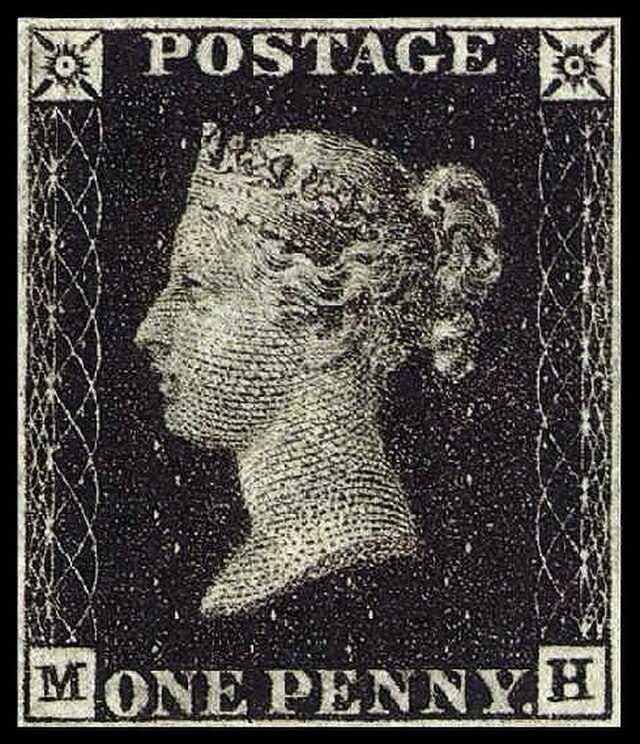

The world’s first self-adhesive postage stamp, the Penny Black, was issued on 6 May 1840 and quickly became a huge success. Hill proposed that it bear an elegant portrait of Queen Victoria by the Royal Mint’s Chief Engraver, William Wyon. The design had appeared on a medal in 1837 commemorating the monarch’s visit to the City of London and was based on a sketch that the artist had made in 1834 when Victoria was fifteen.

The introduction of the Penny Black meant that, for the first time, a letter weighing up to half an ounce (14g) could be sent anywhere in Great Britain or Ireland for just one penny. The stamps were printed onto imperforate sheets of gummed paper so that they could be carefully cut out for sale or use. Each sheet contained 240 stamps in 20 rows of 12 columns. One full sheet cost 240 pence (one pound) and a column of 12 stamps cost a shilling.

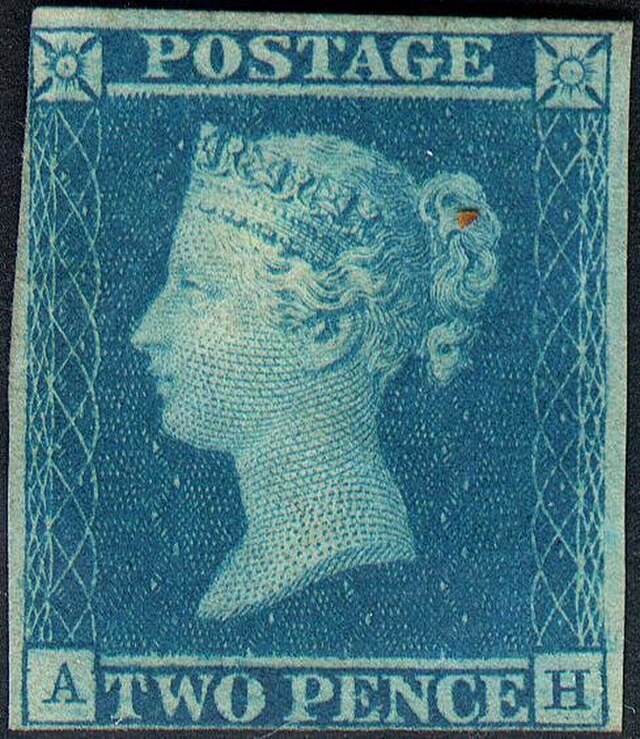

To post letters weighing between half an ounce and an ounce (28g), a customer could purchase a Two Penny Blue stamp, introduced just two days later on 8 May 1840. It featured the same portrait of Queen Victoria but was printed in a striking blue colour and had the words “Two Pence” underneath the portrait instead of “One Penny.”

The two new stamps were designed to be elegant, efficient, and simple to use. They contained anti-forgery measures such as intricate engravings and corner lettering. When a letter arrived in the system for delivery, the stamp would be struck with a Maltese cross cancellation mark to show that it had been used and to prevent it from being reused. At least, that was the theory.

For all its success, the Penny Black remained in use for just a year. Despite its elegance, it had a major design flaw which Hill hadn’t foreseen. The red cancellation mark was hard to see on a black printed stamp, which made it possible for stamps to be reused after they had been postmarked and delivered to their destination. Consequently, in 1841, the Treasury changed the colour of the penny stamp from black to red and issued cancellation devices with black ink, which proved to be easier to see and harder to remove.

The transition from the Penny Black to the Penny Red was a simple yet effective solution to a practical problem, making the postal service far more profitable and efficient, and paving the way for future innovations in the world of postage. The stamp continued to be used on letters and parcels for the next thirty-eight years. In that time, over 21 billion Penny Reds were printed, making it one of the most widely used stamps in British history.

The impact of the Penny Post was immediate and immense. Literacy soared as letter writing became a national pastime. Businesses flourished with faster contract negotiations, and families and friends found a cost effective way to stay connected over long distances. As Hill had predicted, the volume of mail exploded from 76 million letters in 1839 to nearly 350 million by 1850. By the end of the nineteenth century, there were between six and twelve daily mail deliveries in London, enabling people to exchange multiple letters within a single day.

The Penny Post laid the foundation for the modern postal service, introducing innovations like pillar boxes, parcel delivery, mechanised sorting and international air mail. Hill’s genius idea quickly spread throughout the British Empire and across the continents, inspiring similar postal reforms in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia and America.

Today, there is hardly anyone alive who hasn’t experienced the joy of sending and receiving letters and parcels from loved ones in the post. Cherish these special moments by raising a toast to Sir Rowland Hill and his quiet revolution that changed the world for the better.